Sustainable Design Feature: Interview with Dr. Jamie Miller

Originally published in Award

NB: With the release of the IPCC report, what is it that truly stands out to you as a positive to come from it about how we look toward sustainable/innovative design and approaches to help solve the increasing problems we are facing?

JM: I’m most excited to see a focus on the importance of intact ecosystems. My belief is that the most effective (and inexpensive) path for mitigating climate change is to support ecosystem services. In our technological advancements as a species, it seems that we have forgotten that the most effective technologies for carbon sequestration, storm management, energy dissipation, air and water filtration, noise reduction, temperature control, and general environmental stability, is nature.

Why I appreciate biomimicry so much is that it offers a perspective that shifts our lens of the natural world – moving it from something to take from towards something that can teach us. When we start to unveil the incredible solutions that nature has, we start to realize that over billions of years of evolution it has refined effective strategies for how to live/thrive on this planet. It solves many of the same challenges that we face (packaging, manufacturing, material design, “waste” management, agriculture, transportation, organization) but in such a beautiful and sustainable way.

If we can fundamentally shift our interpretation of nature to see its inherent value, and to see it as a mentor of design, then we will truly be on a path of sustainability.

NB: Can you tell us more about a couple of truly the stand-out nature-based solutions out there right now that complement the whole approach to sustainable design? And how is B+H hoping to integrate this into its work (or how has it already of course)?

JM: I believe any project that harmoniously integrates (or blurs the glaring contrast) of the built and natural environments and shifts our perspective, or improves the ecological performance of a site, is a good strategy for moving forward. I appreciate the Eden Project, which turned an unused mine into a biodiverse dome, and I love the CH2 building, which built on earlier work of understanding the efficient cooling techniques of a termite mound to inspire incredibly creative and sustainable building strategies. Other projects of note are the Liuzhou Forest City, the Port of Portland’s Living Machine that treats wastewater on site, indoors, and with only plants.

In an architectural project that we are working on in India, we wanted to go far beyond “doing less harm” to see if we could create a building that was a contribution to its place. We were basing our design on the fact that humans are an integral part of their environment, and that historically, we were a key part of it.

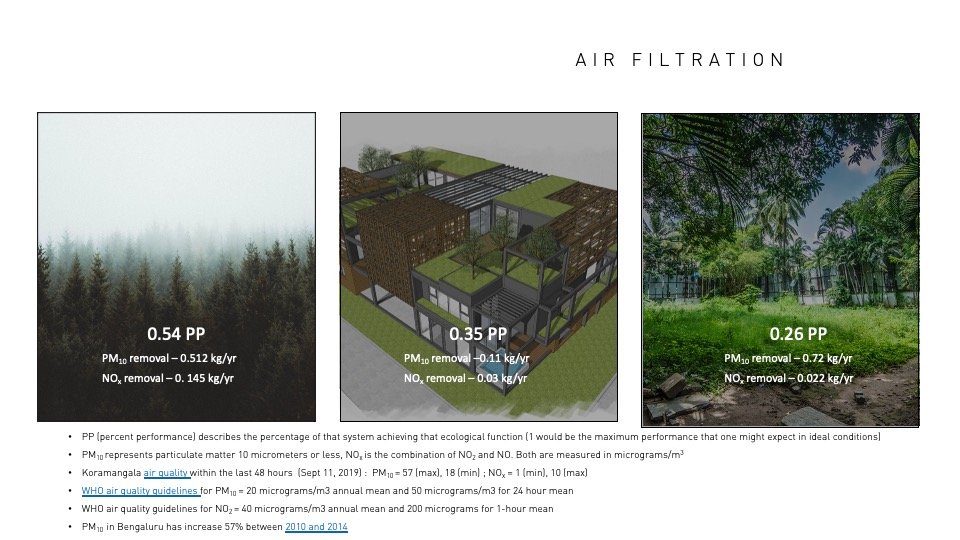

To measure our success, we focused on ecological performance metrics. We measured the ecological performance of the site as is (pre-construction) and compared that to the performance of our proposed design. Overall, our design had better overland flow retention, we increased carbon sequestration, decreased noise and air pollution, produced more oxygen, and decreased the ambient temperature.

To go a step further, we developed a scenario where the area we were designing for had no previous development and was its historical conditions, i.e., an old-growth forest. To truly see how much our design contributed to the site, we measured the performance against this forested scenario to see that although we are better than doing nothing to the site, we could still find deeper innovations to function as efficiently as a forest.

Some key elements of our success included: 30% of the building was under gardens and included an integrated permaculture strategy amongst all the planters and yard. A mycelium soil strategy was developed, where all planters were interconnected, and a “mycelium shaft” was designed to ensure that the mycorrhizae could connect to mother earth and therefore communicate and share resources amongst all the plants. We developed an integrated on-site water harvesting, recycling, and groundwater recharge system that fed the plants. And we focused on ensuring that the embodied and operational carbon costs of the building did not supersede the carbon sequestering capabilities of the building’s lifespan.

NB: Sustainable design in Indigenous Communities isn't something we often read about, which thinking about it now is bizarre! Can you tell us more about what is being done in this area and your involvement?

JM: At my other company, Biomimicry Frontiers, we have an Indigenous Elder on our board who has been a major contributor of our knowledge of biomimicry. When I first told her about the concept of biomimicry she looked and me and said, “Well Jamie, we’ve been doing biomimicry for thousands of years.” And she’s right.

What’s amazing about the concept of biomimicry is that it is not a new idea but that it reflects a way of thinking that has been drowned out and distorted by the dominant cultural thinking of Western Science. That is, there are many communities and cultures that may “think” biomimetically, but for me and the training I’ve received, it was a powerful revelation for how things could (should) be done.

Fundamentally, what this means is that biomimicry reintroduces the idea that nature could be a great teacher. That it is the reflection of brilliant forms, processes and systems that could teach us how to thrive on this planet. It invites us into a conversation with nature that may confront our established paradigms of the natural world. That is, nature doesn’t speak English and we must acknowledge our existing biases of the natural world in order to truly reveal all the genius it has to offer. For example, I was never taught in biology that a tree could pump fluids hundreds of feet in the air without electricity or mechanical pumps. Or, that a spider can make a material with a strength-to-weight ratio stronger than anything humans have created but with only a subset of the periodic table of elements, at body temperature and pressure, and in water-based chemistry. Oh, and often the spider will eat its fully biodegradable and non-toxic silk as a way of promoting circularity. I was never taught these things but the more I walk beside Indigenous People and Traditional Knowledge Holders, the more I realize that biomimicry is very similar to the beliefs of those who have learned to live in harmony with their place. It’s all about reframing the lens and seeing the world through different perspectives.

More practically, we are seeing architects like Two Rows and Douglas Cardinal integrate some of the traditional thinking of their People into design and development. In a project with the Métis Nation of Alberta and Reimagine Architects, we applied our “Living Story” assessment as a way of designing a masterplan that was more in harmony with the site. We sought to learn the natural trajectory of the land (what the land wants to do, would support us in doing, and permit us to do) in order to place infrastructure that more effectively worked with that trajectory rather than trying to fight it or engineer it. The idea was to create a united socio-ecological system that leveraged hidden ecological assets which could reduce engineering costs and improve long-term resilience.

NB: Are there any projects you are working on currently that focus on these areas, or, that showcase B+H's focus on sustainable design?

JM: We are now bringing our methodology to our practice at B+H Architects to guide three land developments in Canada, Gabon, and the Bahamas. We are very excited about these projects because the clients are aligned with our vision of pushing traditional development techniques to allow nature and its trajectory to dictate our designs. We are also continuing work on our architecture design in India and on some more progressive building and interior projects.

NB: What are you excited about this year when it comes to B+H and sustainable design and indeed the industry as a whole?

JM: First, I am very excited that B+H is investing in biomimicry as a bold and sustainable strategy for moving forward. Together, we are finding practical ways of integrating the nature-based philosophy into its suite of existing services, including architecture, master planning, landscape architecture, interior designs, experiential designs, and advanced strategy. What excites me is that together we can create more practical applications to demystify biomimicry and show to the public that it’s an approach that is both sustainable and economically viable.

In my mind, biomimicry can apply to any discipline. There are metaphors in nature that could help us improve any aspect of our way of doing things. And together with the level of talent at B+H, we get to dive deep into nature’s textbook to learn these stories and then together, cleverly find ways for how they can improve our products and processes. We can give clients a fresh approach to a problem. And with today’s “wicked problems” we know that fresh and bold approaches are necessary since we will not solve today’s problems with the same thinking that created them.