SJ Bulletin: Jamie Miller on Unlocking Nature’s Secrets of Sustainability

Originally published in the SJ Bulletin on June 21, 2022.

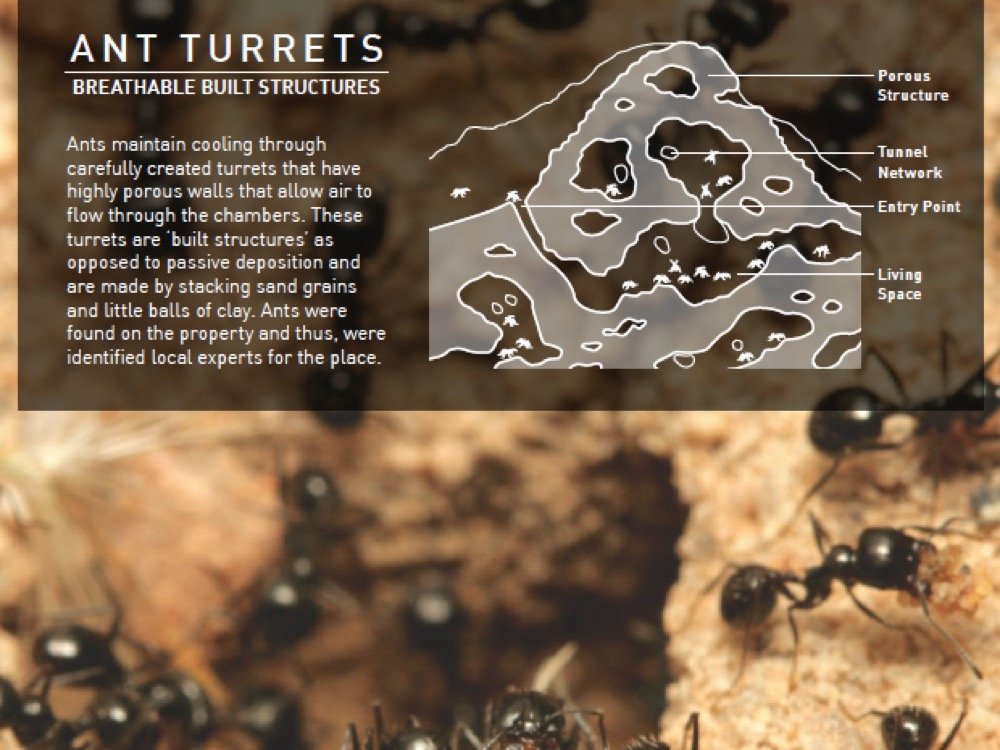

In a house design project in India, Jamie looked at local flora and fauna, namely barrel cactus, elephant skin, termite mounds and ant hills, to design and build better passive cooling strategies. That client, a landowner in Bengaluru, wanted to have his new home immersed in nature. Miller used biomimicry, permaculture and ecological engineering to create a rammed earth primary structure and also emulated termite mounds and forest canopies in addition to the elephant skins to create passive cooling for the home.

As a practitioner of biomimicry, Jamie Miller questions established paradigms within the built environment. “Our designs are formed on the basis of how we interpret nature to work,” he says. “Biomimicry invites us to re-examine our existing knowledge and to determine whether our agriculture, architecture, engineering, and industry are derived from knowledge that is compatible with nature’s own.”

Jamie developed a fascination with the theory of biomimicry early in life, when a math and poetry class at university revealed the beauty of the Fibonacci sequence and the golden ratio, both often expressed in nature.

Biomimicry and engineering

“The magic of biomimicry is in knowing that nature has refined incredible solutions for how to thrive on this planet and in the not knowing of how to necessarily abstract these ideas to the built environment,” Jamie says. It is the not knowing that Jamie is most intrigued by, “We first need to learn nature’s genius and then creatively find ways to emulate those ideas to work more harmoniously with her. There is still so much that we don’t know about the natural world, and I am fascinated every time we learn something new.”

Jamie has a PhD in engineering, focused on systems-level biomimicry and urban resilience, and has been applying biomimicry to the built environment through his consultancy, Biomimicry Frontiers. Last November, he was brought in to B+H to expand that practice with a wider group of experts.

He also founded Biomimicry Commons in 2019, an education and incubation platform to encourage others to bring nature-based philosophy to their own approaches – whether it is design, art, education, politics, technology, or engineering. The Commons is a creative community to help support the growth of more biomimicry applications and encourage more nature-based businesses and solutions. In 2019, Fast Company named it a “World-Changing Idea”.

Levels of biomimicry

For Jamie, biomimicry can be grouped into three levels: Form, process and systems. Form-based biomimicry is about emulating shapes and patterns which commonly appear in nature to improve efficiency, like how wind turbine blades are improved by altering their design to emulate humpback whale fins.

Process-based biomimicry is about understanding and applying natural manufacturing systems. An example is spider silk, which has a strength to weight ratio greater than anything humans have made. He says, “Spiders make this at body temperature and pressure, using water-based chemistry, a subset of the periodic table of elements and only the energy of the sun. And because its manufacturing is benign, it’s fully recyclable – in fact, spiders will often eat their own silk. This deeper level of biomimicry allows us to function more like an ecosystem and move beyond “doing less harm” towards becoming a contribution to our place. So, to deepen the sustainability of a project, I may first look to form but will also explore how we might include things like green chemistry, benign manufacturing, circularity, or additive manufacturing.”

“The deepest and most important level of biomimicry is systems-based. This is where we blur the glaring contrast between the built and natural environments by emulating the deeper principles of how ecosystems function. It’s about reintegrating back into nature and creating conditions that are conducive to more life.”

An example: Prior to B+H, Jamie explored the ways in which nature creates no waste to help build Canada’s First Circular Food Economy in Guelph, Canada. By learning how nature exploits resources and creatively reengineers them, he helped a local brewery turn spent grains into bread and was experimenting with ways of turning spent bread back into beer. He also built a community agriculture patch, based on the ecological principle of patch dynamics. The idea was to focus on integrating backyard gardens so that not everyone was growing the same food and that they could make a more resilient food system by increasing the diversity. Through an app, his neighbourhood now shares, barters and trades amongst themselves accessing a wider variety of food.

Design process

For his work, he starts by understanding the local context. “For example, in master planning projects we always start with a ‘Living Story’ site assessment which defines the socio-ecological trajectory of place. Our goal is to find out the hidden ecological assets and the existing site trajectory so that we can leverage nature’s free resources and build in harmony with the site. We recognize that it can be expensive to fight nature and so we are trying to build resilience by building harmonic designs.”

He follows up by leveraging the design strategies premised on the local context. For example, in the house design in India, he looked at local flora and fauna, namely barrel cactus, elephant skin, termite mounds and ant hills, to design and build better passive cooling strategies.

Nature as a teacher

“The bottom line in my biomimicry process is to break down what it is I want the design to do by identifying the basic function and then ask nature how she would solve that. For example, if I want to create adhesives, I might look at spiders, geckos, burrs, blue mussels, or snails. If I want to make those metaphors inform my design, I figure out exactly how they do it and then find people or technologies that might be able to make a solution that is simple and cost effective.”

But above all, he is adaptive to clients and contexts – like water. As Jamie observed in a recent webinar: “Ecological resilience is like a ball sitting in a bowl of water, the ball being nature, rolls with the water, which represents its environment. . Engineering resilience is more like a cube in that bowl of water – designed to resist change from its environment and fend off that once-in-a-hundred-year storm. Why are we spending so much time and energy resisting nature, rather than using nature, to be resilient?”

“In collaborating with clients, I try to listen as much to the things that they are saying as well as the things they are not. I’m trying to really understand what their perspectives, interpretations, motives, needs, wants, or fears are so that I can best tailor my responses to that. There is no ‘one size fits all’ in communicating biomimicry. Like nature, it’s about being locally attuned and responsive.”

And constantly being in the flow with divergent viewpoints helps designers to challenge assumptions, stay flexible in mind and be creative.

This is where his Biomimicry Commons comes in – like a rich and robust mycelium network that helps a forest to adapt to pests and other changes, the Commons is about creating a network of people who want to shift the paradigm of design through application. “It isn’t just about me sharing ideas, it’s about providing the soil for all practitioners to share their genius and create a richer experience of life,” he says.