Designing with Context: Biomimicry, Biophilia, and the Eco-Centric Model

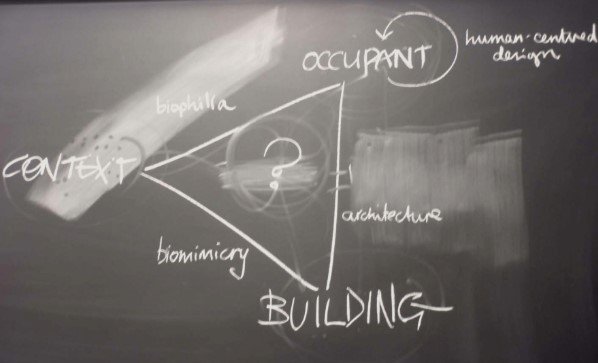

Image from OCAD U’s biomimicry class, describing the basis of eco-centred design (by Carl Hastrich)

In a time of ecological urgency, the need to design in harmony with the environment is more than just good practice—it's an ethical imperative. The Eco-Centric Model repositions design not as an isolated act serving only humans, but as a deeply interconnected process that considers the occupant, the building, and the context in equal measure. At the center of this model is a question—not just of how we design, but who and what we are designing with.

Human-Centered vs. Eco-Centered Design

Traditional human-centered design focuses on optimizing environments for human needs—comfort, efficiency, usability. While this approach has brought innovation, it often treats humans as separate from the ecosystems they inhabit. It risks isolating us from the very places we depend on, designing for people rather than with the world.

The eco-centered design paradigm, by contrast, embraces a broader lens. It recognizes that human well-being is inherently tied to ecological health. In this model, context is not background—context is everything. It is the climate, geology, community, biodiversity, and stories that define a place. Designing with context ensures that our buildings are not only sustainable, but responsive and regenerative.

The Three Threads: Biophilia, Biomimicry, and Architecture

The triangular relationships in the Eco-Centric Model are bridged by three guiding principles: biophilia, biomimicry, and architecture.

1. Biophilia (Occupant ↔ Context)

Biophilia is the innate human tendency to seek connections with nature. This principle connects occupants to their context, acknowledging that psychological and physical health are enriched by exposure to natural patterns, materials, and living systems.

In our work with Indigenous communities, biophilia resonates deeply. Many Indigenous traditions do not view humans and nature as separate. Through the Living Story Methodology, we uncover these narratives embedded in land and culture, allowing design to emerge from place-based wisdom. Biophilic design, in this sense, becomes not just aesthetic—but restorative and relational.

2. Architecture (Occupant ↔ Building)

Architecture is the craft that translates human needs into spatial experiences. It links occupant to building, shaping how people inhabit space. Yet in an eco-centric context, architecture cannot be reduced to form or function alone. It must listen to place, using materials, forms, and systems that resonate with local ecologies and stories.

We see architecture as a bridge—not just between people and buildings, but between cultures, climates, and ways of knowing. When co-designed with Indigenous partners, architecture becomes an act of storytelling, reflecting both the social and ecological narratives of place.

3. Biomimicry (Building ↔ Context)

Biomimicry connects building and context by asking: How does life thrive here? It is the discipline of emulating nature’s strategies—its thermal regulation, structural efficiency, water capture, and resilience.

But biomimicry is more than technical mimicry. It is a philosophy of deep observation and humility. It invites designers to become students of the land, to see the building not as an imposition, but as a participant in a living system. A biomimetic building is one that contributes—harvesting energy like a leaf, filtering water like wetlands, and adapting like a forest.

Living Story: Design as Relationship

Our Living Story Methodology sits at the heart of this model. It recognizes that every place holds a story that is still unfolding—and that design is a continuation of that narrative. This methodology honors Indigenous knowledge systems that see knowledge not as static but living—transmitted through land, ceremony, language, and community.

By integrating Living Story into the Eco-Centric Model, we shift from extraction to relationship. We listen. We co-create. We let context lead.

From Interconnection to Interbeing: Regenerative Design

The Eco-Centric Model moves us toward a new frontier—not just sustainability, but regeneration. This happens when we stop seeing occupant, building, and context as separate entities and begin to understand them as co-creators in a shared ecosystem. When in dialogue, these three elements do not simply function—they dance.

This dance is dynamic and reciprocal:

A building influences how people behave and how energy is used.

Occupants shape the life of the building and how it engages its environment.

Context—the land, the water, the stories—can be honored, degraded, or regenerated through both.

Whether that influence is positive or negative depends on how deeply we listen: to the occupant (through human-centered design), and to the land (through eco-centered design). When both voices are heard, we can create systems that restore ecosystems, heal communities, and reconnect us with place.

Regenerative design is what emerges when we embrace this interbeing. It sees humans as active participants in ecological processes—not separate from nature, but as agents of care, creativity, and stewardship. It is the recognition that design is not just what we do to the world, but what we do with it.

Final Thoughts: Design as a Living Conversation

The center of the Eco-Centric Model—the question mark—is not a void. It is an invitation. It calls us to design from relationship, through reciprocity, and toward regeneration.

In this model, context is not a constraint but a teacher. Occupants are not end users but co-creators. Buildings are not static containers but living participants in the ecology of place.

This is not just a framework—it’s a worldview. One that listens deeply. One that learns continuously. One that invites all beings—human and more-than-human—into the story of design.