Doodling on the Masterpiece

Biomimicry and regenerative design should be about adding to the beauty and abundance of a place, not detracting from it.

Why Design Needs a Deeper Conversation with Nature

(Reflections from the 2025 AZURE Media Human/Nature Conference)

This year at the Azure Human/Nature Conference, Brian Porter of Two Row Architect and I shared a stage and a message: modern design has been “doodling on the masterpiece.”

For decades, our designs have been adding bold strokes of infrastructure on top of a masterpiece we barely understand. We've too often been designing in confrontation with nature, avoiding nature, or worse - building over nature. But what we seldom do is design with her, or within the deeper teachings she carries.

Think, "designing to resist 100-year storm events" instead of "designing to flow or flood". Think landscaped ecosystems vs. complex biodiversity.

And the cost of this superficiality is now showing up everywhere: overheated cities, collapsing biodiversity, flooding neighbourhoods, inequitable growth, and communities spiritually disconnected from the places they call home.

The fact that "regenerative" design has become the latest buzzword in sustainable design confirms that what we've been doing previously has been inherently "degenerative." From my perspective, it's because we have lost the deeper connection to place. We've lost our knowledge of the nuances of nature and the deeper principles of how she behaves. Perhaps we have also lost the effort to put in the time to change that.

As my colleague Gian shares, we need to spend the time learning the brushstrokes, the intention of the original artists, to learn how to add to her beauty. And for centuries now, we've been scribbling on the masterpiece.

On one hand, I can understand why. The socio-ecological systems we are tasked with designing for are complex. They have many variables, increasing uncertainties, and timelines that our brains can't account for. But on the other hand, the consequence of not designing harmoniously is becoming too costly not to.

So how do we move from degenerative to regenerative? To actually become a contribution to the places we design?

For me, that bridge has been biomimicry - a conversation with nature that is helping me remember the genius of place. For Porter, it is just the paradigm he has always known.

The Deeper Principles We Forgot to Ask About

Indigenous partners like Brian, Erik Skouris, Matthew Hickey, and Elder Jean Becker are good to remind me that biomimicry isn’t a trend - it’s a memory. As Elder Becker puts it, her People, "have been doing biomimicry for thousands of years.”

When we treat nature only as a catalogue of forms, as something to engineer or exploit, we miss the real wisdom embedded in relationships, time, reciprocity, pattern, and place. Biomimicry, when practiced deeply, becomes a conversation. It can help us reconnect with the genius of nature - beginning a deeper conversation of how nature could inspire us, guide us, and mentor us in designing regeneratively. We can learn how nature has been solving problems for living on this planet over the long haul. And our job is to interpret those stories. For me, biomimicry becomes a shared language - a place where Indigenous and non-Indigenous worldviews can meet without forcing either to collapse into the other.

This shared language is what guided our collaboration on the George Brown College Campus Masterplan, led by Gail Shillingford , where biomimicry, indigeneity, and sustainability formed a single braided approach.

We didn’t start with engineering. We didn’t start with buildings. We started with the stories we were telling and the language we were using.

Rewriting the Story of Toronto’s Waterfront

One of the most profound insights that emerged - through Two Row’s teachings and our Living Story method - was that Toronto has literally and metaphorically turned its back on the water. Towers ensure most people in the city can't even see one of the Greatest Lakes on the planet. Rivers that once were passages for First Nations are buried underground. We learned about the ancient Lake Iroquois, the original shoreline of Tkaronto that ran right beside George Brown College's Casa Loma Campus. We learned the portage routes, the early ecology, and the life that thrived from the ancient waterways.

Overlay of earlier Tkaronto land on current Toronto shoreline

We learned that water is a sacred teaching - a woman’s teaching. That every one of us began our journey suspended in water in our mother's womb, and that there's deep importance in honouring the water. Yet the city’s development patterns, its towers, and even its educational infrastructure have largely treated water as backdrop, risk, or afterthought.

So we changed the question from: “How can we reduce the risk of water events?” to “How can water - and therefore life - return to the campus?”

This shift opened the door to entirely new design strategies:

1. Bridging Ookwemin Minising

With the massive rewilding Ookwemin Minising project just off the shores of George Brown's Waterfront Campus, we thought of how the mainland could leverage the energy, ideas, and programs of the island - through landscape, university partnerships, curriculum, and even the built forms.

Bridging the designs and design thinking of Ookwemin Minising to bridge the natural and urban environments.

2. Rethinking Waterfront Toronto’s façade

Thinking virtically, thousands of travellers fly past the campus every day as they take off and land at Billy Bishop Airport. One Indigenous Participant imagined bold exterior signage and storytelling that reframe the facade of George Brown's buildings - not as a wall that blocks the lake, but as a living threshold inviting people back to the story of water and Indigenous Ways of Knowing. To blur the built and the natural.

3. Designing with natural forces - solar, wind, and seasonality

We proposed strategies for buildings and landscapes that move with environmental conditions instead of resisting them - exploring how buildings could flood, breathe, and adapt to seasons through strategic engineering and building technologies. Leveraging the genius of Atelier Ten to tune form, processes, and materials to the rhythms of wind, light, and seasonal change.

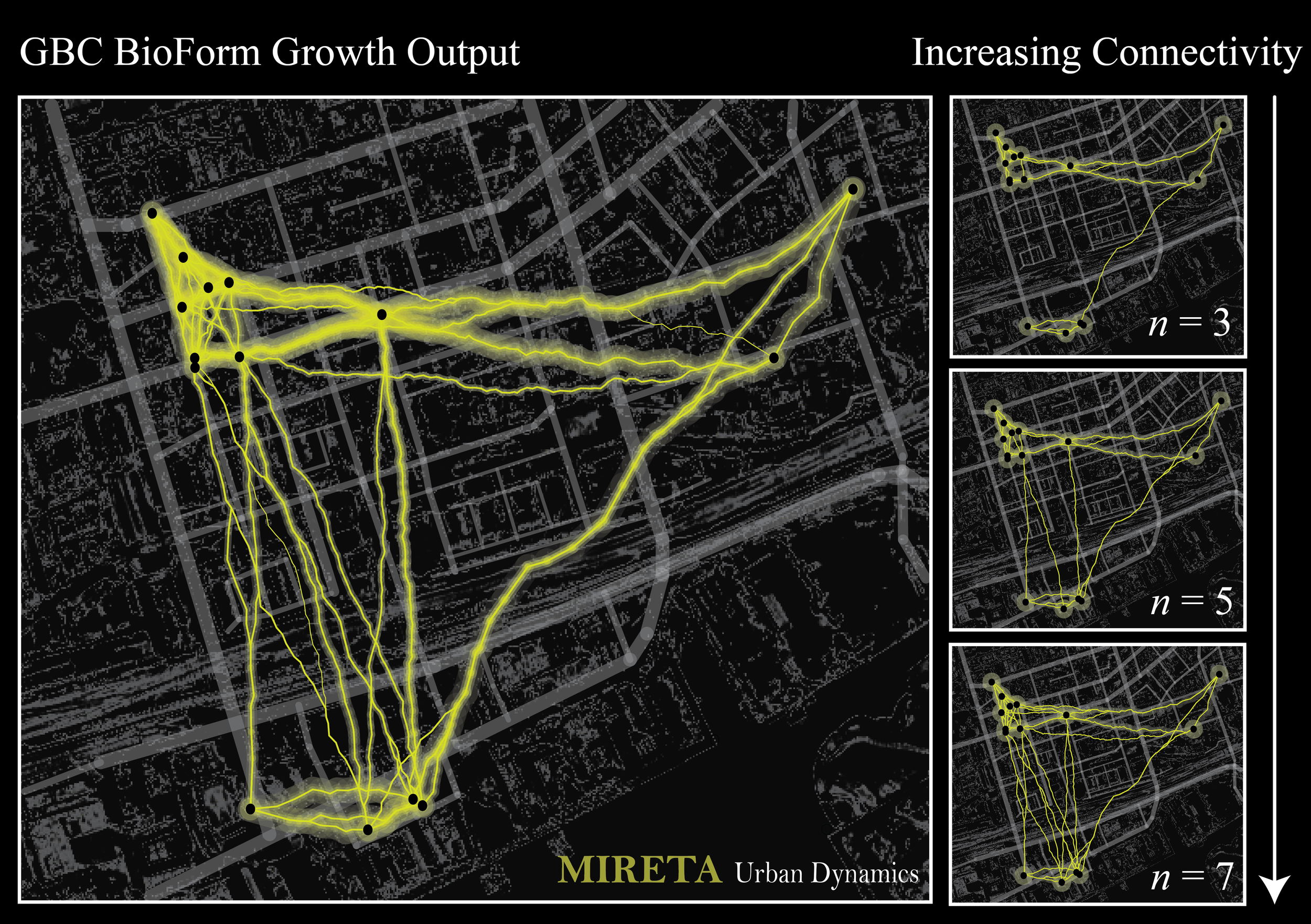

4. Slime mould algorithms as masterplan teachers

Knowing how efficient nature is with materials and circulation, we explored how slime mould behaviour - nature’s genius for optimizing connectivity while minimizing cost - could help us connect GBC’s three distinct campuses with more coherence, efficiency, and place-based logic.

Mireta's slime mould output for material efficiency and resilient circulation for GBC campus

5. A resilience network of green and open spaces

Knowing that nature wants to come into our cities (just imagine if we all left the city, what would happen), we mapped ecological corridors, remnant green spaces, and potential micro-habitats across the city, asking how they could be strengthened and interconnected into a campus-wide resilience strategy.

Reconnecting ecological cooridors for climate resilience and ecological services

6. Embodied carbon as an evolutionary decision lens

Seeing carbon as a building block (as in nature), we assessed the full embodied carbon profile of existing and future GBC buildings, helping the institution understand whether to build new, refurbish, repurpose, or gracefully decommission - based on ecological and temporal wisdom, not just capital costs.

Across every one of these interventions, the same principle held:

When we change the story, the design changes.

The Real Power of Biomimicry Isn’t Design - It’s Relationship

The more I do this work, the more I realize biomimicry is not a technical discipline. It’s a relationship discipline.

It gives me a language to ask better questions. A method to see patterns I've forgotten how to notice. A way to slow down enough to hear what the land is already doing.

And perhaps most importantly, it offers a shared space where Indigenous and non-Indigenous practitioners can work together without one worldview dominating the other - something that was beautifully demonstrated in our joint workshop with Two Row and Atelier Ten, gathered around maps of buried rivers, talking circles, and student stories.

This is how a campus becomes a teacher. This is how a city becomes a living system again. This is how we stop doodling - and start contributing.

Thank you, Brian, Erik and Matthew, for showing me a story of a Tkaronto that has long been buried, but that I hope to one day see reemerge through collaborative design with a renewed lens.