How an Elephant Quietly Rewrote Our Cooling Strategy

Image by Geraninmo: https://unsplash.com/@geraninmo

How Design Fiction, Elephant Skin, and One Question Shift Are Rewriting the Future of Cooling

Most design briefs start with a familiar question:

“What do we want to design?”

It sounds innocent. But that one question quietly drags the past into the future. It pulls on what we already know how to do, the materials we always use, the systems we already trust - even when we know they’re no longer appropriate for us, or the planet.

For our work in biomimicry and regenerative design, we’ve learned to ask a different question:

“What do we want our design to do?”

That subtle shift has a dramatic impact. It moves us from form to function, from preconception to purpose. And it opens up an entirely different library of solutions - one that’s been field-tested for 3.8 billion years.

From “What” to “What For”

In 2017, a progressive client invited us to create one of the first truly biomimetic homes. Not just a home with “green features,” but a home guided by a process that helps us think as nature, not just about nature.

We pulled out the functions: how could this building breathe, how could it self-cool, retain rain during monsoons and hold it during droughts, how could it connect, or turn into a forest?

Starting from “What should we design?” would have sent us back to familiar territory - e.g. shading devices, high-performance glass, efficient mechanical systems. All important, but still orbiting the same old paradigm.

So instead we asked:

How does nature stay cool?

What do we want our design to do in thermodynamic terms?

What local strategies could teach us about design in this context?

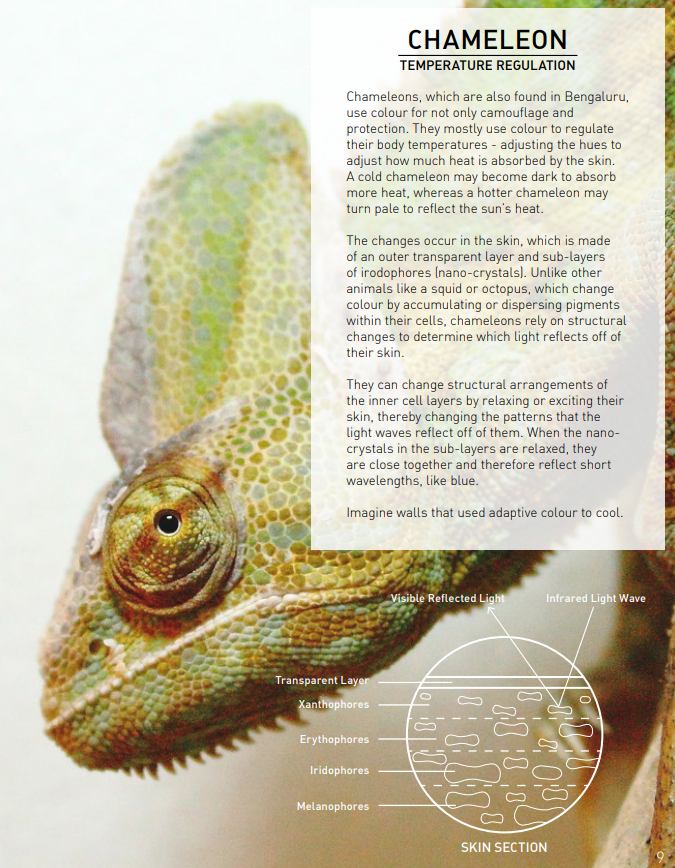

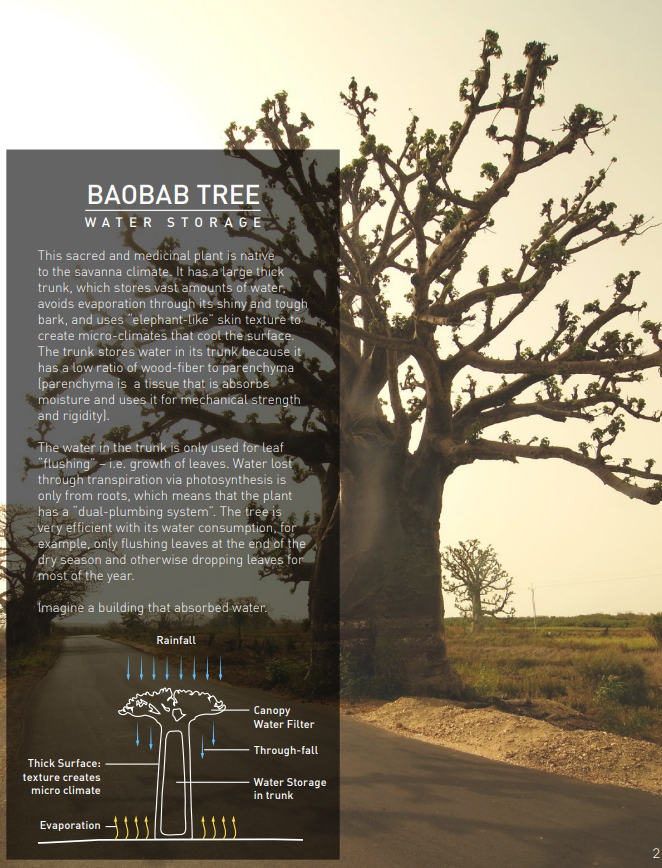

That question led us into the local genius of place. We studied barrel cactus, termite mounds, ant hills, frog skin - natural masters of temperature regulation - hypothesizing how they solved our function. We captured each strategy in what we called Bio-Data Sheets: visual pages that translate biological wisdom into design possibilities meant “to develop bio-inspired ideas that may not yet be possible, but that provoke a conversation of what could be, or should be, possible.”

We created our design fiction.

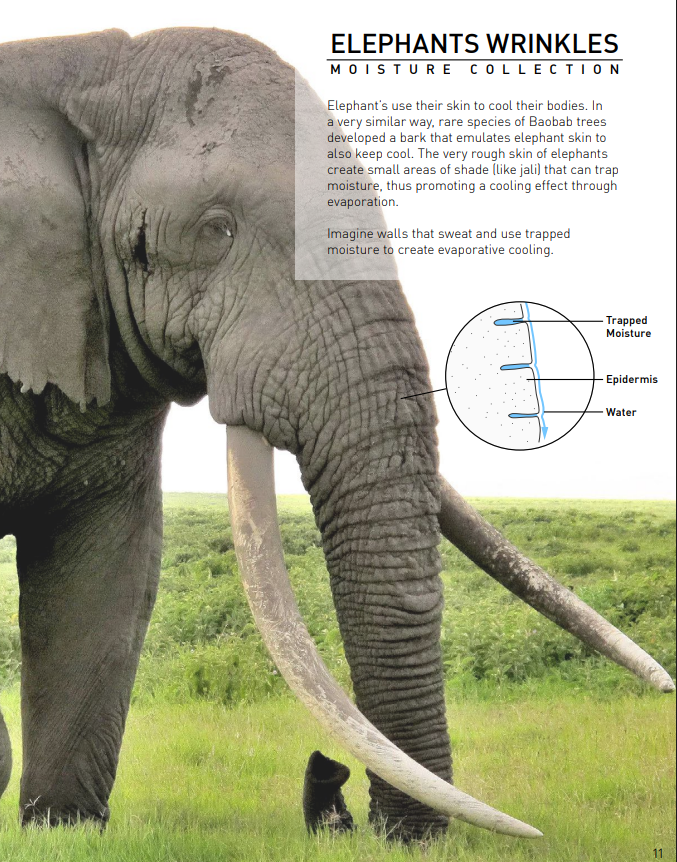

Biodata sheet exploring elephant wrinkles for passive cooling.

Biodata sheet exploring chameleons as thermal regulation inspiration

Biodata sheet exploring the storage and retention strategy of a baobab tree

Those early explorations were not construction drawings. They were seeds and ways of asking, “If nature can do this here, what would it look like if our building could too?”

When an Elephant Becomes a Cooling Strategy

One of those seeds came from an unlikely mentor: the elephant.

To us, an elephant and a building shared commonalities: a lot of exposed surface area dealing with a lot of heat. So we asked, How does an elephant keep cool without air conditioning?

Of course, we noticed the ears, but we became curious about the elephant's wrinkles and that perhaps their skin was part of their passive cooling strategy. We could see that the grooves trapped thin films of water and mud, protecting moisture from evaporating too quickly. The tiny shaded pockets allowed evaporation - and therefore cooling - to continue long after the sun has moved on.

So we posed a new, very simple design-fiction question:

What if a building’s walls could “sweat” like an elephant?

I’m not a biologist. I actually dropped out of biology in grade ten because I thought it lacked inspiration. But surrounded by a diverse team, we didn’t need to be experts in every species. We needed to be experts in abstraction: translating biological function into design intent.

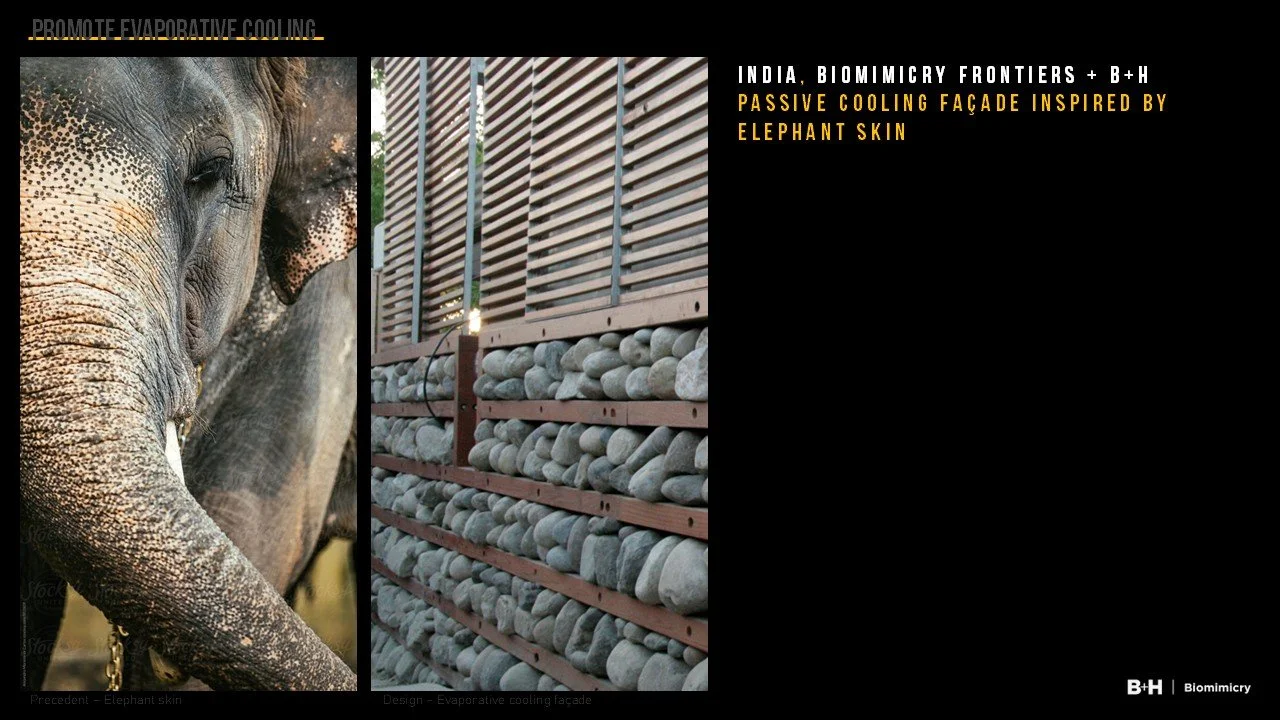

So, as designers, ecologists, engineers, farmers, landscape architects, and architects, we started to abstract the biological function into design, resulting in a rock-wall façade concept that could act as a second skin for the building.

Rainwater, harvested from the roof, could trickle over stacked stones. The gaps between rocks would behave like “wrinkles,” creating shade and slowing evaporation. As water gradually evaporated off the surface, it would cool the surrounding air—just as it does on an elephant.

No exotic materials. No expensive lab-grown composites. Just stone, gravity, and rainwater arranged with intention.

Elephant wrinkle design translation

Was it a fully proven system? Not yet. But the physics made sense. The idea was inexpensive to build. And most importantly, it expanded the conversation about what cooling could be.

From Idea to Cascading Impact

At that stage, the elephant-skin façade was still conceptual. But I believe in the power of concepts to act like seeds in a potential forest of innovation.

One of our team members carried the idea forward, evolving it into a natural wall panel with similar principles. Designers in Singapore then began experimenting with mycelium-based materials shaped to mimic elephant skin, pushing the idea into new material territory.

Mycelium-based wall tiles inspired by elephant skin

More recently, researchers have published peer-reviewed studies showing that surfaces inspired by elephant skin can significantly enhance evaporative cooling by 25% compared to smooth walls, increasing to 70% during rain conditions - demonstrating that what began as design fiction is not only possible, but in some cases better than conventional approaches.

This is what excites me most about biomimicry:

We’re not just copying shapes from nature. We’re seeding trajectories of research, technology, and design that keep unfolding long after the first sketch.

A speculative wall detail in a 2017 project can help spark a chain of prototypes, experiments, and papers that may influence how we cool buildings around the world. That’s the quiet power of asking, “What do we want our design to do?” and then turning to life for answers.

The Real Barrier: Our Thinking

People often tell me biomimicry sounds beautiful but impractical. Too complicated. Too expensive. Too “out there.”

But the elephant-skin story starts suggests the opposite.

The first move wasn’t a new material or a huge R&D budget. The first move was a different question. The second was paying attention to how nearby organisms already answer it. The rest was creative translation.

If we want designs that truly support the generations coming after us, we have to be radically conscious of the thinking we use at the start. Because our thoughts are not abstract. Our thoughts become forms. We are living today inside the physical manifestations of yesterday’s assumptions.

Right now, we are seeding the forests of our future - creating the worlds our grandchildren will live in. Biomimicry helps us be good ancestors by inviting the wisdom of Earth’s oldest elders - 3.8 billion years of experimentation - to guide those seeds.

The elephant-skin façade began as an idea that didn’t quite fit within the boundaries of “normal” practice. But it provoked a question, then a conversation, and now a growing body of evidence: nature’s cooling strategies are not just poetic; they are measurably effective.

Thinking Naturally, Creating Naturally

For me, this is the heart of biomimicry and regenerative design:

We shift from “What do we want to design?” to “What do we want our design to do?”

We invite nature in as model, measure, and mentor.

We use early design phases - like our Bio-Data Sheets - not just to document, but to imagine what’s possible.

We accept that even speculative ideas can set off cascades that reshape what’s considered “realistic.”

Biomimicry is closer than you think. It’s not locked in a lab. It’s in the questions you ask, the organisms you choose to learn from, and the courage you have to let those insights change the brief.

If we learn to think naturally, we will inevitably create naturally. And in doing so, we stand a much better chance of becoming the kind of ancestors our descendants - and the rest of life on Earth - deserve.